Volume VIII | Issue 2

Poetry in the time of calamity.

In this issue are poems written before the contagion’s spread. Poems which will survive after it passes.

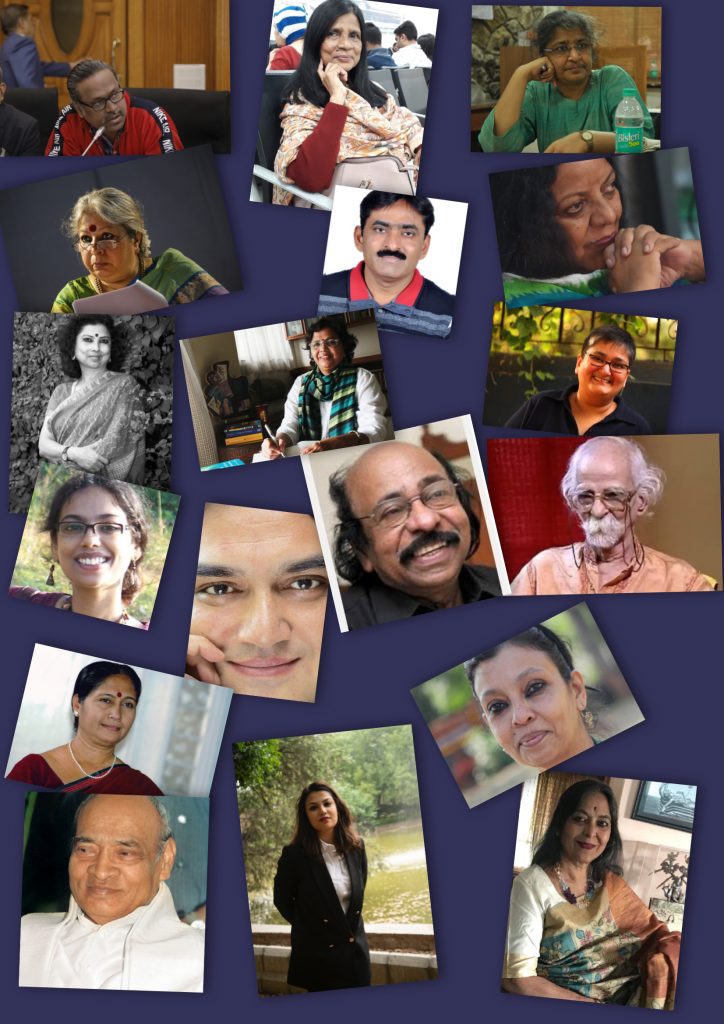

We are fortunate to have Dr. Savita Singh, a truly remarkable poet, feminist, theorist and teacher as our guest editor. She gifts us the translated work of six women poets who write in various Indian languages. Read Dr. Savita Singh’s work here, translated by poet Medha Singh.

Control and rebellion circulate between translation, the body politic and the politics of the body: the breath our words emerge from, the womb in which we make our words; the bodies of women who make these verses and those of the translators who conceive them in another tongue; and the torque of power between the languages. Politics of belonging play out behind the printed page, emerging as they do in different times/ places/ rhythm of privilege or oppression, yet always alongside the body of beauty and spirit, which affirms its creation.

Thinking of the process of rethinking literature, especially poetry, in another language, I wonder what ‘dies’ in translation? Or does the poem transmute, alchemizing its cells into different poetic structures in the host language? What remains after the act of translation, and what is remade? Does the translation rise phoenix -like through the original poem’s body which blazes on in its landscape? The two like twin flames that are not identical reflections of each other as they shimmer in different skies.

I question the translators’ axiom: to recreate the original in a fervent and colloquial target language, which here is Indian English. For instance, some translations stay true to the sense of duration of the original, in their preference for using the continuous tense, whether past or present. As in ‘has been’ or ‘is coming’, that reflects a roll of unceasing time. Is the translator being true when she substitutes the above phrases with ‘was’ or ‘comes’, which is considered more ‘acceptable’ in English usage? Does a world tilt on its axis when this is done? Does an ocean weep? How many are the possibilities that exist, via translation, to world the fullness of the source world? Perhaps you’d like to expand on these exciting problematics in your practice, as writers, translators, active readers.

We increasingly need translations as we live in a global world which is bound by more than deadly panic and numerous segregations. We need to read more work by more women, to fill out our understanding of our worlds. And ourselves.

On another note, we bid goodbye to our magnanimous webmaster, Saurabh Agarwal, who requires to wander into forests of filmmaking, languages, music. Thank you, Saurabh, from the core of my heart, for being smiling, stable support to Poetry at Sangam for three plus years. Working with you is a pleasure, and our good wishes follow you. We extend a very warm welcome to Dr. Yamini Dand Shah, literary researcher and academic advisor and curator, who joins us out of her love for poetry. She takes over as webmaster. Thank you, Yamini.

Read on.

–Priya Sarukkai Chabria

To write. An act which will not only ‘realise the decentred relation of woman to her sexuality, to her womanly being, giving her access to her native strength; it will give her back goods, her pleasures, her organs, her immense bodliy territories which have been kept under seal…(Hélène Cixous, The Laugh of the Medusa in E. Marks and I. de Courtivron (eds.) New French Feminism, Sussex: Harvard Press: 280)

The present issue of Poetry at Sangam is special in at least two ways. First, seven women poets are present here, from different Indian languages; second, they are all in translation in English. It’s a special way to be for a poet: between two simultaneous universes of language and meaning. It’s a way to risk one’s self-understanding, however thin that is today. Literary theory has given us space to breathe, to avoid clinging much to dated ways of creating and realizing meaning. Multiplicity is the way for poets to have a glimpse of what wholeness can mean. It is a multilayered, variegated structure where each one of us can find room for our craft, and be ennobled by the presence of the other at the same time.

The poets included in this issue are Mandakranta Sen (from Bangla, translated by Sudeep Sen), Pratibha Nandkumar (from Kannada, translated by the poet herself), Nirupama Dutt (from Punjabi, translated by the poet herself), Pradnya Pawar (from Marathi, translated by Dileep Chavan, Krishna Kimbahune, Ashok Sahane and Shals Mahajan ), Jayaprabha Anipindi (from Telugu, translated by P.V Narasimha Rao), Pravasini Mahakud (from Odia, translated by K. Satchidanandan) and Savita Singh (from Hindi, translated by Medha Singh). These poets and translators have brought together a world of verse which indicate so much more than how things such as desire, hope, sexuality, and beauty are. Rather, how they are transitioning into some other universe, where one narrates the act of watching, as a young girl-mother making love to her father, pictures of rain, Shiva dancing. A young girl is not what she was just before witnessing this sin, shattering the conception of what truth is and how sexuality liberates, what rain can do to a picture one had of it, before putting its image in the verse.

The possibility of annihilating the other is what poetry politely refuses today. We are all in one space, but the place is reconfigured. Here, there is not one quintessential subject, masculine in its ancient consciousness, and others as its shadows that become parasitical, in transcending it. The phallus is a thing of language only, a symbol of transcendence; it can be understood today as one construction among many others, though placed hierarchically higher. Contemporary feminism has made it possible to rethink and redo our previous world. Put aside the hierarchy secured through binaries of concepts and meanings.

When Priya Sarukkai Chabria invited me to edit the March issue of Poetry at Sangam, I began to think intensely. This opportunity ought to be matched with bringing together unique content. I would like to thank her for agreeing with the idea that we bring together seven women poets in translation. After all, March is a month we celebrate International women’s day. She was thrilled, in fact. She is a poet and fiction writer who often goes on imaginary excursions into speculative fiction. We are together in it, that is. It’s a nice journey where we have exchanged many words and discussed the difficulty of translations. Yet our thirst or desire to understand women in poetry remained undeterred. I know for certain that there is an intimate relationship between language and sexuality and, as women our desires are well kept in here; the desire to know ourselves in spite of and beyond the symbolic order set up by patriarchy. It’s also a way to be liberated from its oppression. Writing poetry is to be a full subject in language, to find oneself as one has not been so far.

Poetry was often thought to be something mysterious, its sources undisclosed to the poet and the reader. The Greeks believed the muse was the source. In India, the words in themselves are the source, as they are “Brahm” in their utterance; in the modern European sense, the source was the unconscious, which is nebulous in its being. The tradition of psychoanalysis has configured it as a secret space where memories of repressed desires pulsate and govern the conscious mind. This discovery has helped women’s poetry in a unique way. As it was not long before its structure became akin to language itself. So, turning to language and writing has led to understanding women’s sexuality like no other move. Writing is desiring, as women do desire, yet they are repressed. One must dig this language deeply, figure out the modes of hierarchization. The hierarchy between the poet and translator is also reflective of the same relationship. Women have known the pain of this shadowy existence for a long time. Till the beginning of the nineteenth century, they could only aspire to be translators, not authors or poets.I offer here a word for the translators of these poems: they have made a difference, I mean, they have attempted to produce the multiplicity of meaning inherent in the poems themselves. They come to us as pulsating with the energies of both the poets and the translators.

I hope it will be possible for our readers to understand through these poems why the metaphor of ‘becoming a woman’ is understood as the demise of truth as known, and the birth of poetry as a play of difference. These poems in their variedness, hopefully, will touch readers and they will not only read them but feel them as an event in their being.

In poetry, one can be a woman without the fear of death or truth. In translation, one can be reborn to enjoy the freedom of bodily organs, many other goods, and their native strength.

– Dr. Savita Singh

MANDAKRANTA SEN translated by SUDEEP SEN

PRADNYA DAYA PAWAR translated by DILEEP V. CHAVAN, KRISHNA KIMBAHUNE, ASHOK SHAHANE and CHAYANIKA SHAH

USHA UPADHYAY translated by RUPALEE BURKE

JAYAPRABHA ANIPINDI translated by P.V. NARASIMHA RAO

PRAVASINI MAHAKUD translated by K. SATCHIDANANDAN

SAVITA SINGH translated by MEDHA SINGH

This site is designed and maintained by GONECASE